Daily Reflection – God Has Given Us a Unique Vocation

416 N 2nd St, Albemarle, NC, 28001 | (704) 982-2910

To follow Christ is an option, a choice, a call, a vocation, and we are totally free to say yes or no or maybe. You do not have to do this to make God love you. That is already taken care of. You do it to love God back and to love what God loves and how God loves!

—from the book Eager to Love: The Alternative Way of Francis of Assisi by Richard Rohr, OFM

//Franciscan Media//

Christianity isn’t an abstract philosophy. It’s a complete way of life. Consequently, profession of belief in Christianity isn’t simply an intellectual nod of the head, but a commitment to live in such a way as to express concretely one’s convictions in the everyday world. Such engagement demands a sense of direction, a sense of individual mission and purpose. This is supplied by the particular vocation each of us is given. When we discover our own unique calling, regardless of what it may be, we find the spiritual true north by which to plot our course.

— from the book Perfect Joy: 30 Days with Francis of Assisi by Kerry Walters

Power cannot, in itself, be bad. It simply needs to be realigned and redefined as something larger than domination or force. Rather than stating that power is bad, the Bible reveals the paradox of power. If the Holy Spirit is power, then power has to be good, not something that is always the result of ambition or greed. In fact, a truly spiritual woman, a truly whole man, is a very powerful person. In people like Moses, Jesus, and Paul, we can assume that it was precisely their powerful egos that God used, built on, and transformed, but did not dismiss. If we do not name the good meaning of power, we will invariably be content with the bad, or we will avoid our powerful vocation.

— from the book Things Hidden: Scripture as Spirituality by Richard Rohr, OFM

//Franciscan Media//

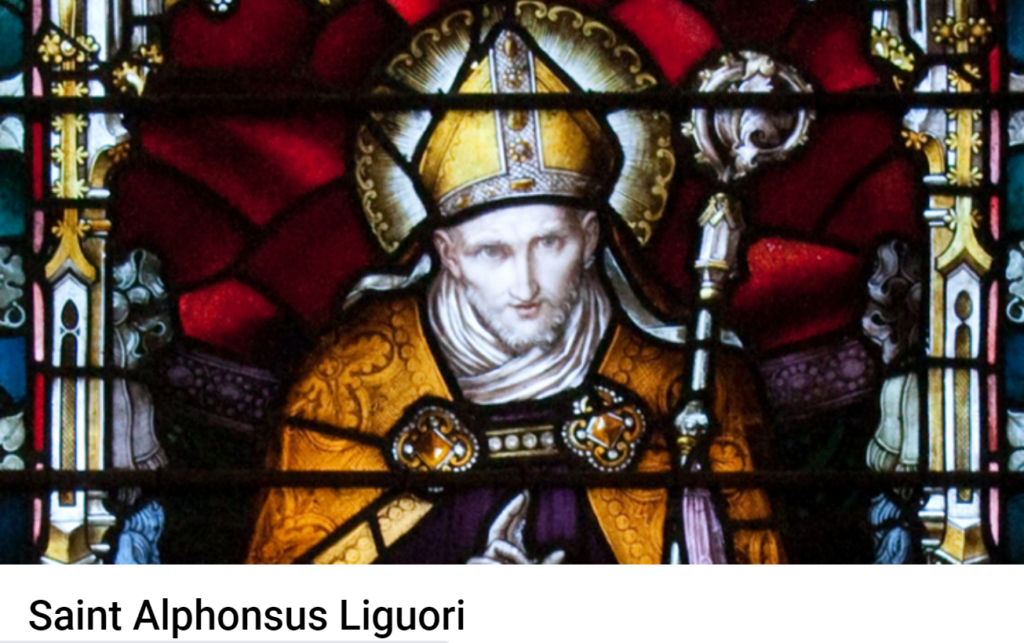

Moral theology, Vatican II said, should be more thoroughly nourished by Scripture, and show the nobility of the Christian vocation of the faithful and their obligation to bring forth fruit in charity for the life of the world. Alphonsus, declared patron of moral theologians by Pius XII in 1950, would rejoice in that statement.

In his day, Alphonsus fought for the liberation of moral theology from the rigidity of Jansenism. His moral theology, which went through 60 editions in the century following him, concentrated on the practical and concrete problems of pastors and confessors. If a certain legalism and minimalism crept into moral theology, it should not be attributed to this model of moderation and gentleness.

At the University of Naples, Alphonsus received a doctorate in both canon and civil law by acclamation, at the age of 16, but he soon gave up the practice of law for apostolic activity. He was ordained a priest, and concentrated his pastoral efforts on popular parish missions, hearing confessions, and forming Christian groups.

He founded the Redemptorist congregation in 1732. It was an association of priests and brothers living a common life, dedicated to the imitation of Christ, and working mainly in popular missions for peasants in rural areas. Almost as an omen of what was to come later, he found himself deserted after a while by all his original companions except one lay brother. But the congregation managed to survive and was formally approved 17 years later, though its troubles were not over.

Alphonsus’ great pastoral reforms were in the pulpit and confessional—replacing the pompous oratory of the time with simplicity, and the rigorism of Jansenism with kindness. His great fame as a writer has somewhat eclipsed the fact that for 26 years he traveled up and down the Kingdom of Naples preaching popular missions.

He was made bishop at age 66 after trying to reject the honor, and at once instituted a thorough reform of his diocese.

His greatest sorrow came toward the end of his life. The Redemptorists, precariously continuing after the suppression of the Jesuits in 1773, had difficulty in getting their Rule approved by the Kingdom of Naples. Alphonsus acceded to the condition that they possess no property in common, but with the connivance of a high Redemptorist official, a royal official changed the Rule substantially. Alphonsus, old, crippled and with very bad sight, signed the document, unaware that he had been betrayed. The Redemptorists in the Papal States then put themselves under the pope, who withdrew those in Naples from the jurisdiction of Alphonsus. It was only after his death that the branches were united.

At 71, Alphonsus was afflicted with rheumatic pains which left incurable bending of his neck. Until it was straightened a little, the pressure of his chin caused a raw wound on his chest. He suffered a final 18 months of “dark night” scruples, fears, temptations against every article of faith and every virtue, interspersed with intervals of light and relief, when ecstasies were frequent.

Alphonsus is best known for his moral theology, but he also wrote well in the field of spiritual and dogmatic theology. His Glories of Mary is one of the great works on that subject, and his book Visits to the Blessed Sacrament went through 40 editions in his lifetime, greatly influencing the practice of this devotion in the Church.

Reflection

Saint Alphonsus was known above all as a practical man who dealt in the concrete rather than the abstract. His life is indeed a practical model for the everyday Christian who has difficulty recognizing the dignity of Christian life amid the swirl of problems, pain, misunderstanding and failure. Alphonsus suffered all these things. He is a saint because he was able to maintain an intimate sense of the presence of the suffering Christ through it all.

Saint Alphonsus Liguori is the Patron Saint of:

Theologians

Vocations

//Franciscan Media//

“What is a vocation? It is a gift from God, so it comes from God. If it is a gift from God, our concern must be to know God’s will. We must enter that path: if God wants, when God wants, how God wants. Never force the door.”

— St. Gianna Molla

//Catholic Company//

It doesn’t take much looking in our economy to see that in fact there is a great deal of work that doesn’t pray, work that disconnects us from our sources of life rather than moves us toward wholeness. For work to pray, it must have a sense of vocation attached to it—we must feel some calling toward that work and the wholeness of which it is a part, that there is something holy in good work. Vocation is a calling and prayer is a call and response, deep calling to deep. For work to pray, to be vocation, it must be brought into a larger conversation. “The idea of vocation attaches to work a cluster of other ideas, including devotion, skill, pride, pleasure, the good stewardship of means and materials,” Wendell Berry writes. It is these “intangibles of economic value” that keep us from viewing work as “something good only to escape: ‘Thank God it’s Friday.’”

— from the book Wendell Berry and the Given Life

by Ragan Sutterfield

//Franciscan Media//