Father Stu – Boxer Turned Catholic Priest

In this hour-long special, actor and director Mark Wahlberg talks to Fr. Mark about his new movie, “Father Stu,” and the incredible life and legacy of Fr. Stuart Long, the boxer turned Catholic priest who inspired it.

Saint of the Day – February 24 – Blessed Thomas Maria Fuscoaka Tommaso

Blessed Thomas Maria Fusco, also known as Tommaso, (1831-1891) was born to a noble and pious family in Italy, the seventh of eight children. He was orphaned at an early age and raised by his uncle, a priest, who oversaw his education. He had a deep love for the faith, especially to the Passion of Christ and Our Lady of Sorrows. He became a priest at the age of 24 and opened a school in his own home. He later became an itinerant missionary throughout southern Italy. After traveling for a number of years he opened another school, this time to train priests on how to be good confessors. He also founded the Priestly Society of the Catholic Apostolate to support the missions, which gained papal approval. During his work with the poor he discerned a call to start a new religious order of sisters, the Daughters of Charity of the Most Precious Blood, to minister to orphaned children. In addition to all of this, Fusco was also a parish priest, a confessor to a group of cloistered nuns, and a spiritual father to a lay group at the nearby Shrine of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. He died of liver disease at the age of 59. He was beatified by Pope St. John Paul II in 2001. His feast day is February 24.

Saint of the Day – February 11 – Blessed Bartholowmew of Olmedo

Blessed Bartholomew of Olmedo (1485-1524) was a Spanish Mercedarian priest, and the first priest to arrive on Mexican soil in 1516 at the age of 31. He was chaplain for the expedition of Spanish Conquistador Fernando Cortés, who began the Spanish colonization of the Americas and the downfall of the Aztec empire. Bartholomew was well-liked by the native people. He taught them the Christian faith and exhorted them to end their practice of human sacrifice. He also defended them against injustice and restrained Cortés from acting out in violence against them. Bartholomew taught the native Mexicans devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary under the title of Our Lady of Mercy, which they embraced. Blessed Bartholomew of Olmedo baptized more than 2500 people before he died in Mexico in 1524 at the age of 39. He was buried in Santiago de Tlatelolco. His feast day is February 11.

//Catholic Company//

Saint of the Day – January 28 – Saint Thomas Aquinas

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) was born into a wealthy and noble family in Aquino, Italy. He was the pious and brilliant son of a count, and a lucrative future was planned for him. When Thomas set off to enter the newly founded Dominican order to be a poor mendicant friar, his mother held him prisoner in the family castle in order to dissuade him. His brothers tried to destroy his purity, and thus his vocation, by tempting him with a prostitute. However Thomas resisted and turned to God for help; as a result, angels were sent to guard and preserve his chastity. This long ordeal only strengthened his vocation, and eventually he escaped and joined the Dominicans. He was ordained to the priesthood and went on to become a famed professor and prolific writer. His works remain immensely influential in philosophy and theology, the most famous being his Summa Theologica, and multiple popes have upheld him as the model of a systematic Catholic education. St. Thomas Aquinas is the foremost Doctor of the Catholic Church, known as the “Angelic Doctor” for his purity of mind and body, and remarkable intelligence. St. Thomas Aquinas is the patron of schools and universities, students, philosophers, theologians, apologists, academics, and chastity. His feast day is January 28.

//Catholic Company//

Saint of the Day – January 29 – Saint Aquilinus of Milan

St. Aquilinus of Milan (d. 1015 A.D.), also known as St. Aquilinus of Cologne, was born to a noble family in Bavaria, Germany. He received his education in Cologne, Germany and was ordained to the priesthood. He was offered the bishopric of Cologne, but turned it down in order to be a missionary priest and itinerant preacher. He traveled through various European cities fighting against the dangerous and spreading heresies of the Cathars, Manichaeans, and Arians. He was also known to work miracles by healing people from disease, especially during a cholera epidemic. He eventually settled in Milan, Italy, and was so effective in his preaching against the Arian heretics that they stabbed him to death and threw his body in the city sewer. His body was recovered and buried in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, in a chapel which now bears his name. His feast day is January 29.

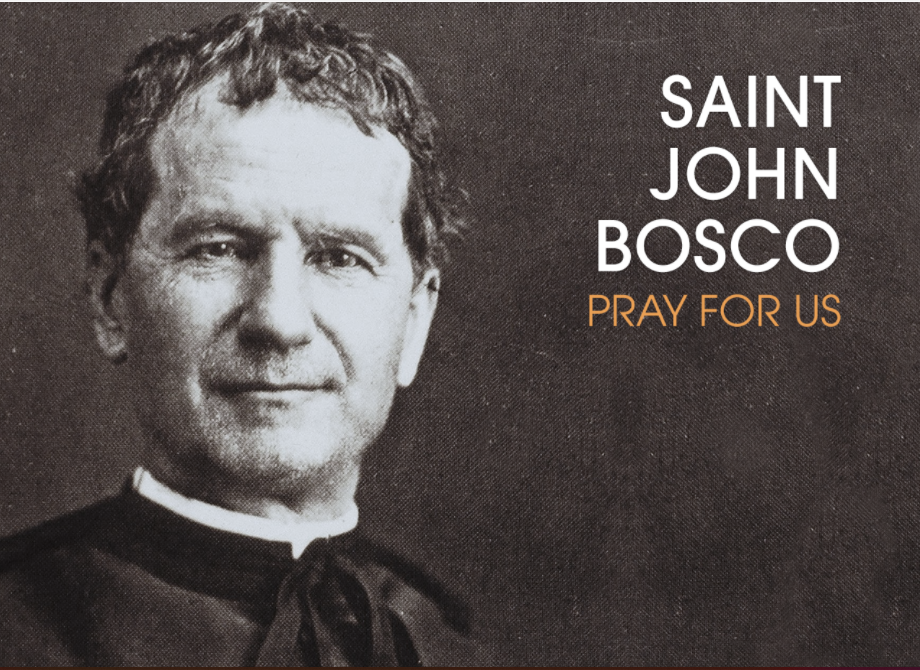

Saint of the Day – January 31 – Saint John Bosco

Saint John Bosco’s Story

John Bosco’s theory of education could well be used in today’s schools. It was a preventive system, rejecting corporal punishment and placing students in surroundings removed from the likelihood of committing sin. He advocated frequent reception of the sacraments of Penance and Holy Communion. He combined catechetical training and fatherly guidance, seeking to unite the spiritual life with one’s work, study and play.

Encouraged during his youth in Turin to become a priest so he could work with young boys, John was ordained in 1841. His service to young people started when he met a poor orphan in Turin, and instructed him in preparation for receiving Holy Communion. He then gathered young apprentices and taught them catechism.

After serving as chaplain in a hospice for working girls, Don Bosco opened the Oratory of St. Francis de Sales for boys. Several wealthy and powerful patrons contributed money, enabling him to provide two workshops for the boys, shoemaking and tailoring.

By 1856, the institution had grown to 150 boys and had added a printing press for publication of religious and catechetical pamphlets. John’s interest in vocational education and publishing justify him as patron of young apprentices and Catholic publishers.

John’s preaching fame spread and by 1850 he had trained his own helpers because of difficulties in retaining young priests. In 1854, he and his followers informally banded together, inspired by Saint Francis de Sales.

With Pope Pius IX’s encouragement, John gathered 17 men and founded the Salesians in 1859. Their activity concentrated on education and mission work. Later, he organized a group of Salesian Sisters to assist girls.

Reflection

John Bosco educated the whole person—body and soul united. He believed that Christ’s love and our faith in that love should pervade everything we do—work, study, play. For John Bosco, being a Christian was a full-time effort, not a once-a-week, Mass-on-Sunday experience. It is searching and finding God and Jesus in everything we do, letting their love lead us. Yet, because John realized the importance of job-training and the self-worth and pride that come with talent and ability, he trained his students in the trade crafts, too.

Saint John Bosco is a Patron Saint of:

Boys

Editors

Educators/Teachers

Youth

//Catholic Company//

Saint of the Day – January 26 – Saint Timothy

St. Timothy (1st c.) was born in Galatia in Asia Minor, the son of a Greek father and a Jewish mother. Timothy was a convert of St. Paul the Apostle around the year 47 A.D. Timothy became a trusted friend and a beloved spiritual son to Paul, laboring faithfully alongside him in his apostolic work for many years. Paul mentions Timothy repeatedly in his letters and dispatched him on important missionary work to the local churches he founded. Timothy was ordained to the priesthood at the hands of St. Paul and was later made bishop of Ephesus. St. Timothy was stoned to death thirty years after St. Paul’s martyrdom for having denounced the worship of the false goddess Diana. St. Timothy is the patron of intestinal and stomach problems, because Paul admonished him to ease his penance and drink a little wine for the sake of his health, instead of only water. His feast day is January 26.

Saint of the Day – January 24 – Saint Francis de Sales

Saint Francis de Sales’ Story

Francis was destined by his father to be a lawyer so that the young man could eventually take his elder’s place as a senator from the province of Savoy in France. For this reason Francis was sent to Padua to study law. After receiving his doctorate, he returned home and, in due time, told his parents he wished to enter the priesthood. His father strongly opposed Francis in this, and only after much patient persuasiveness on the part of the gentle Francis did his father finally consent. Francis was ordained and elected provost of the Diocese of Geneva, then a center for the Calvinists. Francis set out to convert them, especially in the district of Chablais. By preaching and distributing the little pamphlets he wrote to explain true Catholic doctrine, he had remarkable success.

At 35, he became bishop of Geneva. While administering his diocese he continued to preach, hear confessions, and catechize the children. His gentle character was a great asset in winning souls. He practiced his own axiom, “A spoonful of honey attracts more flies than a barrelful of vinegar.”

Besides his two well-known books, the Introduction to the Devout Life and A Treatise on the Love of God, he wrote many pamphlets and carried on a vast correspondence. For his writings, he has been named patron of the Catholic Press. His writings, filled with his characteristic gentle spirit, are addressed to lay people. He wants to make them understand that they too are called to be saints. As he wrote in The Introduction to the Devout Life: “It is an error, or rather a heresy, to say devotion is incompatible with the life of a soldier, a tradesman, a prince, or a married woman…. It has happened that many have lost perfection in the desert who had preserved it in the world.”

In spite of his busy and comparatively short life, he had time to collaborate with another saint, Jane Frances de Chantal, in the work of establishing the Sisters of the Visitation. These women were to practice the virtues exemplified in Mary’s visit to Elizabeth: humility, piety, and mutual charity. They at first engaged to a limited degree in works of mercy for the poor and the sick. Today, while some communities conduct schools, others live a strictly contemplative life.

Reflection

Francis de Sales took seriously the words of Christ, “Learn of me for I am meek and humble of heart.” As he said himself, it took him 20 years to conquer his quick temper, but no one ever suspected he had such a problem, so overflowing with good nature and kindness was his usual manner of acting. His perennial meekness and sunny disposition won for him the title of “Gentleman Saint.”

Saint Francis de Sales is the Patron Saint of:

Authors

Deafness

Journalists

Writers

//Franciscan Media//

Saint of the Day – January 10 – Saint William of Bourges

St. William of Bourges (1155–1209), also known as St. William the Confessor, was born to a noble family in France. He was educated under his uncle who was an archdeacon, and from a young age turned away from the world and gave himself over to religion and learning. He became a priest and later entered religious life in a Cistercian monastery, an order famous for strict discipline. St. William was known to be a cheerful man and a hard worker, and pure of heart. He was chosen to be Archbishop of Bourges in the year 1200, much to his dismay. He left the solitude of the monastery out of obedience and entered into the public life of a bishop, throwing himself wholeheartedly into serving both the spiritual and physical needs of the poor. As bishop he continued his great austerities. He had a great devotion to the Blessed Sacrament and would spend much time in prayer at the foot of the altar. He was known for performing miracles both during his life and after his death. He died kneeling at prayer, and by request was buried wearing his hair shirt and lying in ashes. His feast day is January 10.

//Catholic Company//